- Home

- William Lanouette

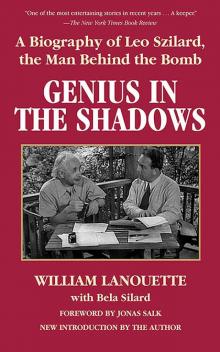

Genius in the Shadows

Genius in the Shadows Read online

GENIUS IN

THE SHADOWS

A Biography of Leo Szilard,

the Man Behind the Bomb

GENIUS IN

THE SHADOWS

A Biography of Leo Szilard,

the Man Behind the Bomb

WILLIAM LANOUETTE

WITH BELA SILARD

Foreword by JONAS SALK

Copyright © 2013 by William Lanouette

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62636-023-5

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-62636-378-6

Printed in the United States of America

To my parents

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

T. S. ELIOT,

“The Hollow Men”

Contents

Illustrations

Introduction to the 2013 Edition

Foreword by Jonas Salk

Preface

PART ONE (1898–1933)

1 The Family

2 View from the Villa

3 Schoolboy, Soldier, and Socialist

4 Scholar and Scientist

5 Just Friends

6 Einstein

7 Restless Research and the Bund

8 A New World, a New Field, a New Fear

9 Refuge

PART TWO (1933–1945)

10 “Moonshine”

11 Chain-Reaction “Obsession”

12 Travels with Trude

13 Bumbling toward the Bomb

14 “I Haven’t Thought of That at All”

15 Fission + Fermi = Frustration

16 Chain Reaction Versus the Chain of Command

17 Visions of an “Armed Peace”

18 Three Attempts to Stop the Bomb. . .

19 . . . And Two to Stop the Army

PART THREE (1946–1964)

20 A Last Fight with the General

21 A New Life, an Old Problem

22 Marriage on the Run

23 Oppenheimer and Teller

24 Arms Control

25 Biology

26 Beating Cancer

27 Meeting Khrushchev

28 Is Washington a Market for Wisdom?

29 Seeking a More Livable World

30 La Jolla: Personal Peace

Epilogue

Chronology of Leo Szilard’s Life

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Illustrations

First Photo Insert

Leo Szilard at about age five

Louis Szilard, Leo’s father

Leo Szilard’s mother with one-year-old Leo

Bela, Leo, and Rose Szilard

The Vidor Villa, where Leo grew up

Leo Szilard in 1916

A Vidor family holiday in Austria

“Cooling the Passions,” a humorous pose with relatives and friends Leo Szilard’s 1919 passport photo

Leo Szilard at a field artillery barracks during World War I

Alice Eppinger

Leo Szilard in the 1920s

Leo Szilard with friends at Lecco, Lake Como, Italy, in 1926

Gertrud (Trude) Weiss

Leo Szilard in England in 1936

Leo Szilard and Ernest O. Lawrence at the 1935 American Physical Society meeting in Washington, DC

Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard in a 1946 March of Time film

The creators of the world’s first nuclear chain reaction pose in December 1946

Eugene Wagner and Leo Szilard in Manhattan in the late 1930s

Leo Szilard testifying before the House Military Affairs Committee in October 1945

Members at the Carnegie Institution’s annual theoretical physics conference, spring 1946

Second Photo Insert

Leo Szilard in Wading River State Park, June 1948

Leo Szilard at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Founders of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists at the Institute for Leo Szilard with Cyrus Eaton at the first Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs in July 1957

Leo Szilard in the Rocky Mountain National Park in the 1950s

Aaron Novick and Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard as sketched by Eva Zeisel

Leo Szilard on the Atlantic City boardwalk, March 1948

Leo Szilard with Jonas Salk

Leo Szilard with Matthew Meselson and Leslie Orgel Leo Szilard with Trude at Memorial Hospital, 1960

Leo Szilard at a Pugwash conference banquet in Moscow, November 1960 Szilard with Inge Feltrinelli in Italy Jacques Monod and Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard at the Dupont Plaza Hotel in Washington, DC

Caricature of Leo Szilard in a bathtub by Robert Grossman

Leo Szilard reading to a young girl

Henry Kissinger, Leo Szilard, and Eugene Rabinowitch

Eleanor Roosevelt and Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard with Michael Straight

Leo Szilard with Francis Crick and Jonas Salk, spring 1964

Szilard speaking at a Salk Institute seminar, February 1964

Leo Szilard’s ashes at Kerepsi Cemetery in Budapest

Leo Szilard’s tombstone at Lake View Cemetery in Itaca, New York

Introduction

to the 2013 Edition

Nearly half a century after Leo Szilard’s death, and two decades after this biography’s first edition, Leo Szilard remains, by and large, an obscure figure for the public. Not so for historians and many scientists, however; his ideas and spirit still offer us helpful scientific, political, and moral perspectives—and a few surprises.

In Szilard’s political satire The Voice of the Dolphins, he imitated Edward Bellamy’s utopian science-fiction novel Looking Backward by predicting correctly in 1961 how the US-Soviet nuclear arms race would wind down in the late 1980s. Nuclear weapons still imperil humanity, but now in newly bizarre ways that defy the Cold War’s deadly logic. Szilard would applaud one Cold War outcome as—all too slowly—nuclear arsenals are being put to better use. In debates during the 1960s about whether to test nuclear weapons, Szilard joked that you should test them! Test them all! Every last one! That never happened, but by 2012, the weapons-grade uranium equivalent of 18,000 Russian warheads had been recycled into fuel for US nuclear power plants by the Megatons to Megawatts Program. And he would still urge nuclear powers to test them all!

On the fiftieth anniversary of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1995, scientists who strived to control nuclear weapons were honored when the Nobel Peace Prize went to the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs and its founding leader Joseph Rotblat. Szilard had helped start Pugwash in 1957, then fostered its approach of candid, private intellectual discourse am

ong scientists, insinuating, he said, the “sweet voice of reason” to the nuclear arms race. He was one of its most ardent members.

But in 1995 a new history revealed how Szilard’s influence had spread unforeseen but decisive results—not by intellectual discourse but by humor. With tongue in cheek but still in moral earnest, Szilard had unknowingly inspired the Russian H-bomb designer Andrei Sakharov to become a champion for arms control and human rights. This tale begins in 1947, when Szilard wrote the political satire “My Trial as a War Criminal” to dramatize how scientists are responsible for their creations: in his case, the A-bomb. Historian Richard Rhodes wrote in Dark Sun, his 1995 history of the H-bomb, that when Szilard’s satire was republished in 1961, Sakharov read it in translation and embraced its moral imperative, prompting the heroic political activism that earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975.

Szilard’s influence was explained by Sakharov’s friend and colleague, Viktor Adamsky, who had translated the satire. “We were amazed by [Szilard’s] paradox,” Adamsky told Rhodes. “You can’t get away from the fact that we were developing weapons of mass destruction. We thought it was necessary. Such was our inner conviction. But still the moral aspect of it would not let Andrei Dmitrievich [Sakharov] and some of us live in peace.” In this way, Rhodes disclosed, Szilard’s story “delivered a note in a bottle to a secret Soviet laboratory that contributed to Andrei Sakharov’s courageous work of protest that helped bring the US-Soviet nuclear arms race to an end.”

Adamsky so admired Szilard that when he read Genius in the Shadows, he decided to translate it and had it published in Russia. In his introduction, Adamsky praised Szilard’s “deep feeling of responsibility for the consequences which could follow from the uncontrolled use of scientific research.” Citing both nuclear weapons and nuclear power, Adamsky called Szilard “a man who at each stage of development foresaw and understood the technological and political aspects of the problem more quickly and more clearly than others. This is one of those rare cases when the work of someone with no official political role substantially affected world politics.” (, 2003).

Also in 1995, a fiftieth-anniversary program at the National Archives in Washington brought together three Manhattan Project scientists who had signed Szilard’s July 1945 petition to President Truman, raising moral questions about using the new weapon. (In all, 155 scientists signed it, and in a poll the Army took, 83 percent of them favored a demonstration before bombing cities.) This petition was also highlighted in 2005, when in John Adams’ opera “Doctor Atomic,” about J. Robert Oppenheimer and the A-bomb, scientists at the Los Alamos nuclear weapons lab distribute and debate Szilard’s petition. Szilard is portrayed occasionally in documentaries and docudramas about the bomb in film, television, and documentaries. His effort to prevent the use of atomic weapons at the end of World War II, by confronting President Truman’s mentor James F. Byrnes, is now dramatized in “Uranium + Peaches,” a play by Peter Cook and myself.

Gently and gradually, the genius that was Leo Szilard has emerged from the shadows. Szilard’s centenary was celebrated grandly in his hometown of Budapest in 1998, and also in the United States. A Leo Szilard Centenary International Seminar at Eötvös University included praise by several Nobel laureates, colleagues, family, friends, and scholars. In his honor, a countrywide “Leo Szilard Physics Competition” was established for high school students, requiring contestants to use computers and conduct laboratory tests to solve modern physics problems. At Columbus, Ohio, that year the American Physical Society celebrated Szilard’s centenary with a seminar at its annual meeting.

In Budapest, a commemorative stamp appeared in 1998 to honor Szilard’s birth, and a plaque was mounted by the entry to the apartment building in Pest where he was born, at 50 Bajza Utca. In the city’s historic Kerepesi Cemetery, a formal service featured Hungary’s Minister of Culture and Education as Szilard’s ashes were interred in the section reserved for members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. “Today his countrymen see Leo Szilard as a latter-day Erasmus coming home at the end of decades of wandering,” the minister said. “Just like Erasmus centuries before him, he had the courage to send letters to chief executives of Great Powers when at stake was how to do good for, or save the peace of the world.” And like Erasmus, “Szilard considered peace to be the most valuable asset of humanity.”

In retrospect, Szilard’s humanity was more aggressive and abrupt than that of Erasmus. Although both men were humanists who dabbled in diplomacy, Szilard was not always diplomatic, and at times he could be downright rude. His faith in rigorous reason sometimes blinded him to life’s random emotional forces and to the feelings of others. The brilliant logic he applied to the chess-like arms race between the USA and USSR now seems passé against militant terrorists seeking nuclear materials to blow up or contaminate cities. Too, Szilard’s profound episodes of self-absorbing thought—he called it “botching”—alienated both family and colleagues. He suffered neither fools nor other geniuses gladly, and this attitude left him with many distant admirers but few close friends. Szilard’s need since childhood to be different and disruptive, played out in science and in politics, kept him from gaining the support that institutions might have offered to reinforce his creative efforts and enhance his reputation. In an unfortunate way, Szilard’s whole creative style led him to the forefront of science but left him by the wayside of society. Although not a “mad scientist,” he could be maddening.

And yet, despite his personal quirks, Szilard’s moral views have radiated through many media. He was bold enough to write a personal version of the Ten Commandments, and in 1992 physicist Freeman Dyson used them as epigraphs in From Eros to Gaia, his book on science and society. Szilard’s second commandment describes his own life: “Let your acts be directed toward a worthy goal but do not ask if they will reach it; they are to be models and examples, not means to an end.” Szilard’s own exemplary ways prompted the editor of the National Academy of Sciences quarterly Issues in Science and Technology to write in 1997 about “the power of the individual” in public life. “The key to Szilard’s effectiveness and influence was that his sense of responsibility for making the world a better place compelled him to work so hard to advance his ideas,” wrote Kevin Finneran. “What Szilard did was to approach public policy with the same rigor, determination, and persistence with which good scientists approach science. What works in advancing science can also work in improving policy.”

Szilard’s creations survive around the world as well. From his ideas and insights to create the European Molecular Biology Organization, there is now a Szilard Library at EMBO’s European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany. Each year since 1974, the American Physical Society awards the Leo Szilard Lectureship Award “to recognize outstanding accomplishments by physicists in promoting the use of physics for the benefit of society in such areas as the environment, arms control, and science policy.”

Szilard was also remembered and praised in London, in 2008, at a seventy-fifth-anniversary celebration and conference for the Council for Assisting Refugee Academics, which Szilard helped found and run in 1933 as the Academic Assistance Council. In the keynote address, medical scientist Sir Ralph Kohn noted how “Szilard somehow always turned up at the right place and at the right time in the 1930s—a true man of destiny . . “Esther Simpson, Szilard’s colleague at the Council in the 1930s, saw him as a “bird of passage” alighting to share his fears and foresight.

Throughout his life, Szilard created institutions for the public good. Politically, his most successful was the Council for a Livable World, America’s first political action committee to raise campaign funds for Senate and House candidates who favor arms control and disarmament. The Council celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2012, with a record of helping elect 120 candidates to the Senate and 203 to the House of Representatives, and that year raised more than $2 million for candidates’ campaigns.

For all his benefits to the commonweal, Szilar

d is still remembered best as a creative and ingenious scientist, first in physics and then in biology. In 1996 the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Akron announced: “Statistical mechanics, nuclear engineering, genetics, molecular biology and political science—Leo Szilard tackled them all. However, it is for his nuclear fission reactor that Szilard joins co-inventor Enrico Fermi in the National Inventors Hall of Fame.” A 1997 Scientific American article and a 2009 Discovery television series on twentieth-century science featured the Einstein/Szilard refrigerator, which the two colleagues designed in the 1920s with an electromagnetic pump to circulate liquid-metal coolant. Too noisy for household use, their concept has long appealed to engineers: first, for cooling nuclear breeder reactors since the 1950s, and recently appearing as small-scale working models built by Malcolm McCulloch at Oxford University and Andy Delano at Georgia Tech.

Szilard’s contribution to what became “information theory”—the study and application of how data and ideas can be codified and shared—is still applied by researchers today. Szilard’s 1923 doctoral thesis took on the thermodynamic puzzle known as “Maxwell’s Demon,” and in a 1929 paper he described how entropy (disorder in a system) affects the use of information. He conceived what is called today “The Szilard Engine,” a process for manipulating molecules, and its use continues to engage and challenge researchers. Physicist Mark Raizen and his colleagues at the University of Texas, Austin, use it to separate isotopes and control atoms in small groups or even individually. The continuing interest in Szilard’s seminal concepts for information theory is credited and well explained in Maxwell’s Demon 2 Entropy, Classical and Quantum Information, Computing (Institute of Physics Publishing, 2003).

In biology, Szilard worked as an “intellectual bumblebee” according to French molecular biologist Francois Jacob. With Jacques Monod and Andre Lwoff, Jacob shared a 1965 Nobel Prize for research on the human immune system based on ideas they credit to Szilard. “Szilard is extraordinary,” said Jacob, “an incredible, surprising man. He had ten ideas a minute. He had ideas about everything.”

Genius in the Shadows

Genius in the Shadows